What is Maxwell (unit)?

The maxwell (symbol: Mx) is the CGS (centimeter–gram–second) unit of magnetic flux (Φ). It is a unit name honors James Clerk Maxwell, who presented a unified theory of electromagnetism.

The maxwell is a non-SI unit.

1 maxwell = 1 gauss × cm2

That is, one maxwell is the total flux across a surface of one square centimeter perpendicular to a magnetic field of strength one gauss.

The weber is the related SI unit of magnetic flux, which was defined in 1946.

1 maxwell = 10−8 weber

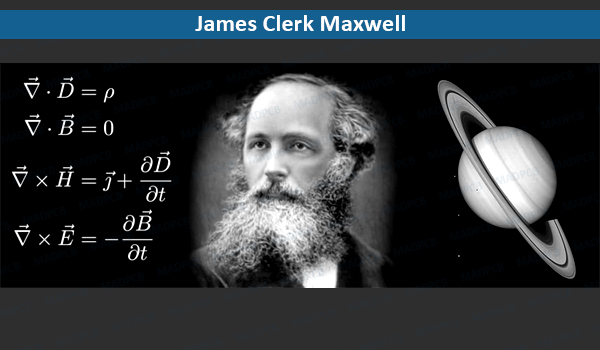

Introduction of James Clerk Maxwell

James Clerk Maxwell, (born June 13, 1831, Edinburgh, Scotland—died November 5, 1879, Cambridge, Cambridgeshire, England), Scottish physicist best known for his formulation of electromagnetic theory. He is regarded by most modern physicists as the scientist of the 19th century who had the greatest influence on 20th-century physics, and he is ranked with Sir Isaac Newton and Albert Einstein for the fundamental nature of his contributions. In 1931, on the 100th anniversary of Maxwell’s birth, Einstein described the change in the conception of reality in physics that resulted from Maxwell’s work as “the most profound and the most fruitful that physics has experienced since the time of Newton.”

James Clerk Maxwell

The concept of electromagnetic radiation originated with Maxwell, and his field equations, based on Michael Faraday’s observations of the electric and magnetic lines of force, paved the way for Einstein’s special theory of relativity, which established the equivalence of mass and energy. Maxwell’s ideas also ushered in the other major innovation of 20th-century physics, the quantum theory. His description of electromagnetic radiation led to the development (according to classical theory) of the ultimately unsatisfactory law of heat radiation, which prompted Max Planck’s formulation of the quantum hypothesis—i.e., the theory that radiant-heat energy is emitted only in finite amounts, or quanta. The interaction between electromagnetic radiation and matter, integral to Planck’s hypothesis, in turn has played a central role in the development of the theory of the structure of atoms and molecules.

Early Life

Maxwell came from a comfortable middle-class background. The original family name was Clerk, the additional surname being added by his father, who was a lawyer, after he had inherited the Middlebie estate from Maxwell ancestors. James was an only child. His parents had married late in life, and his mother was 40 years old at his birth. (See Researcher’s Note: Maxwell’s date of birth.) Shortly afterward the family moved from Edinburgh to Glenlair, the country house on the Middlebie estate.

His mother died in 1839 from abdominal cancer, the very disease to which Maxwell was to succumb at exactly the same age. A dull and uninspired tutor was engaged who claimed that James was slow at learning, though in fact he displayed a lively curiosity at an early age and had a phenomenal memory. Fortunately, he was rescued by his aunt Jane Cay and from 1841 was sent to school at the Edinburgh Academy. Among the other pupils were his biographer Lewis Campbell and his friend Peter Guthrie Tait.

Maxwell’s interests ranged far beyond the school syllabus, and he did not pay particular attention to examination performance. His first scientific paper, published when he was only 14 years old, described a generalized series of oval curves that could be traced with pins and thread by analogy with an ellipse. This fascination with geometry and with mechanical models continued throughout his career and was of great help in his subsequent research.

At age 16 he entered the University of Edinburgh, where he read voraciously on all subjects and published two more scientific papers. In 1850 he went to the University of Cambridge, where his exceptional powers began to be recognized. His mathematics teacher, William Hopkins, was a well-known “wrangler maker” (a wrangler is one who takes first-class honors in the mathematics examinations at Cambridge) whose students included Tait, George Gabriel (later Sir George) Stokes, William Thomson (later Baron Kelvin), Arthur Cayley, and Edward John Routh. Of Maxwell, Hopkins is reported to have said that he was the most extraordinary man he had ever met, that it seemed impossible for him to think wrongly on any physical subject, but that in analysis he was far more deficient. (Other contemporaries also testified to Maxwell’s preference for geometrical over analytical methods.) This shrewd assessment was later borne out by several important formulas advanced by Maxwell that obtained correct results from faulty mathematical arguments.

In 1854 Maxwell was second wrangler and first Smith’s prizeman (the Smith’s Prize is a prestigious competitive award for an essay that incorporates original research). He was elected to a fellowship at Trinity, but, because his father’s health was deteriorating, he wished to return to Scotland. In 1856 he was appointed to the professorship of natural philosophy at Marischal College, Aberdeen, but before the appointment was announced his father died. This was a great personal loss, for Maxwell had had a close relationship with his father. In June 1858 Maxwell married Katherine Mary Dewar, daughter of the principal of Marischal College. The union was childless and was described by his biographer as a “married life…of unexampled devotion.”

In 1860 the University of Aberdeen was formed by a merger between King’s College and Marischal College, and Maxwell was declared redundant. He applied for a vacancy at the University of Edinburgh, but he was turned down in favor of his school friend Tait. He then was appointed to the professorship of natural philosophy at King’s College, London.

The next five years were undoubtedly the most fruitful of his career. During this period his two classic papers on the electromagnetic field were published, and his demonstration of color photography took place. He was elected to the Royal Society in 1861. His theoretical and experimental work on the viscosity of gases also was undertaken during these years and culminated in a lecture to the Royal Society in 1866. He supervised the experimental determination of electrical units for the British Association for the Advancement of Science, and this work in measurement and standardization led to the establishment of the National Physical Laboratory. He also measured the ratio of electromagnetic and electrostatic units of electricity and confirmed that it was in satisfactory agreement with the velocity of light as predicted by his theory.

Later Life

In 1865 Maxwell resigned his professorship at King’s College and retired to the family estate in Glenlair. He continued to visit London every spring and served as external examiner for the Mathematical Tripos (exams) at Cambridge. In the spring and early summer of 1867, he toured Italy. But most of his energy during this period was devoted to writing his famous treatise on electricity and magnetism.

It was Maxwell’s research on electromagnetism that established him among the great scientists of history. In the preface to his Treatise on Electricity and Magnetism (1873), the best exposition of his theory, Maxwell stated that his major task was to convert Faraday’s physical ideas into mathematical form. In attempting to illustrate Faraday’s law of induction (that a changing magnetic field gives rise to an induced electromagnetic field), Maxwell constructed a mechanical model. He found that the model gave rise to a corresponding “displacement current” in the dielectric medium, which could then be the seat of transverse waves. On calculating the velocity of these waves, he found that they were very close to the velocity of light. Maxwell concluded that he could “scarcely avoid the inference that light consists in the transverse undulations of the same medium which is the cause of electric and magnetic phenomena.”